The Memory Building and Architecture as Memento

A deep dive into how architecture responds to memory through usage of precedent, historical revival styles, preservation, and adaptive reuse.

Architecture is an odd discipline in that it can be both transient and lasting. Some works of architecture have been preserved for hundreds or even thousands of years, while others are demolished just ten years after construction. Nonetheless, design is closely intertwined with memory. Through precedents, revivalism, architectural preservation, and adaptive reuse, the memory of historic and classical architecture is maintained. Buildings often tell a story: the city that was, the city that is, and the city that will be.

The Memory Building

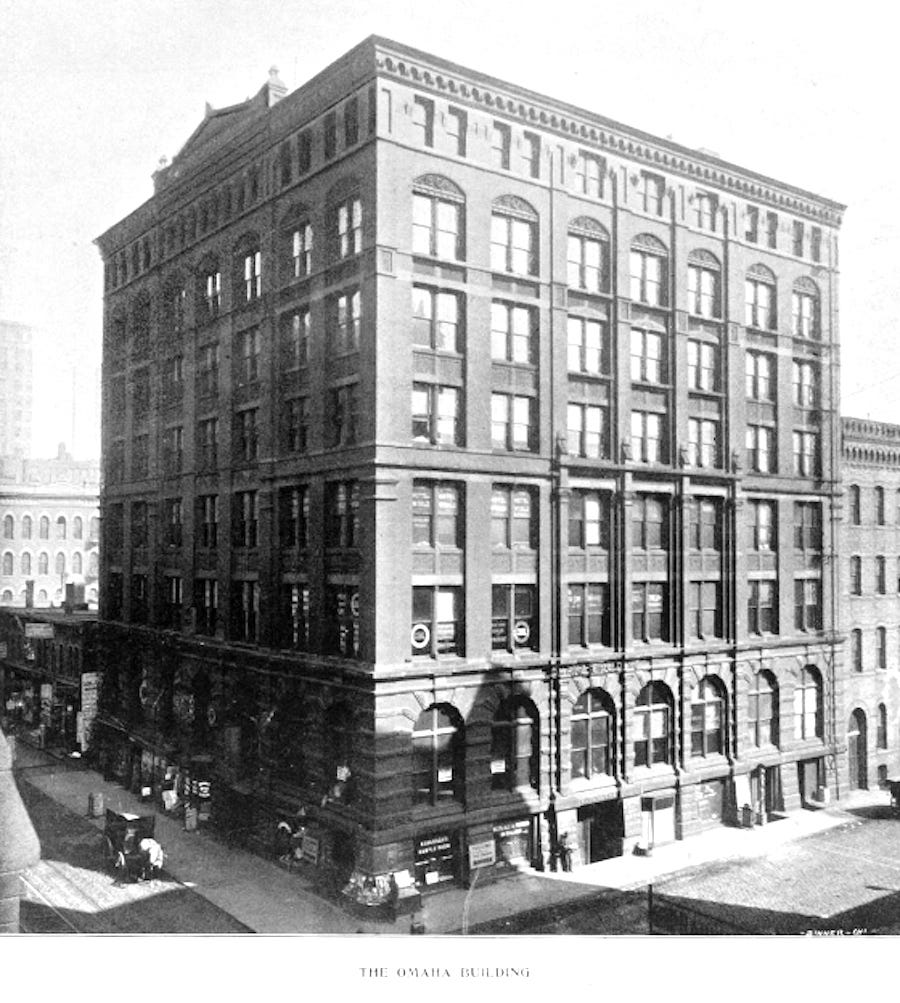

While pondering the term “memory,” I recalled an odd work of Chicago architecture known as the “Memory Building.” Built in 1884 in Chicago’s Printer’s Row neighborhood by architect J. M. Van Osdel, the Memory Building was a typical Chicago School office building. It was built on land purchased by Henry Memory, though it was also known as the “Omaha Building” and “Exchange Building.”

The Memory Building was demolished in 1913 for the construction of the LaSalle Hotel, which in turn was razed in the 1970s for the present 2 North LaSalle skyscraper.

Although the Memory Building is long gone and little more than a footnote in the architectural history of Chicago, we can analyze the case of the Memory Building and how architecture inherently has the past embedded within it.

Architecture as Memento — Precedents

Many works of architecture are directly influenced by designs that came before them. This manifests itself in various stages of legibility. Let’s begin by looking at two much different works of architecture:

This is Walhalla, a Greek Revival monument designed by Leo von Klenze. It is an overt recreation of a classical Greek temple, mirroring the Doric order, proportions, and materiality of ancient Greek architecture. Walhalla’s precedent is obvious.

This is the Lincoln Center for Performing Arts, a New Formalist and Modernist complex designed by various architects. Although these buildings are abstracted and dematerialized, they in fact use the exact same ancient Greek architecture as precedent. New Formalism was an offshoot of the Modernist movement, which sought to achieve a sense of dignity using classical proportions, symmetry, and features like columns and arches.

Walhalla and the Lincoln Center highlight the many varying results that can be achieved through precedents, from clear recreation to heavy abstraction. Although traditional architecture in its most literal sense may be unappealing to a Modernist architect, and vice versa, the principles and spatial organization of those styles can be appropriated for an entirely new work of architecture.

Architecture as Memento — Revivalism

Historical revival styles of architecture fascinate me. It is unusual that there were many points in architectural history where a new style was not consciously being developed. Rather, previous styles were being expanded and improved upon using newer technology.

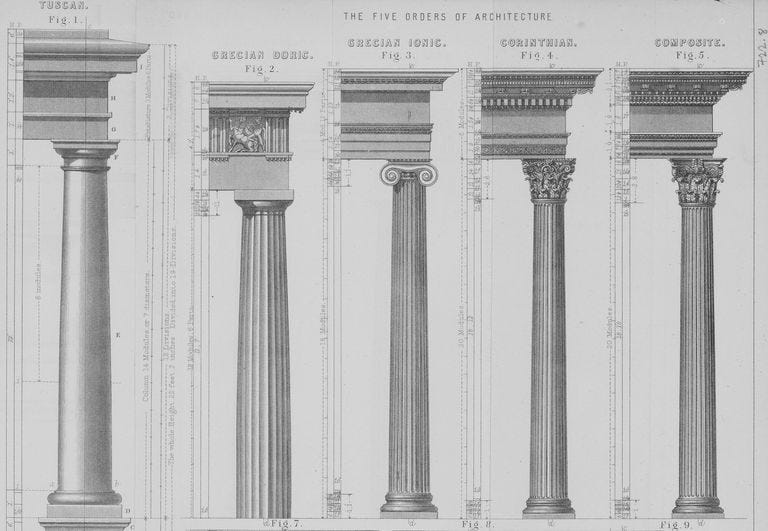

Revivalist architecture is by no means a new phenomenon. You may be familiar with the Victorian-era and Romanticist tendency to design in the long-defunct Romanesque and Gothic styles, for example. However, the earliest example of appropriating an older style of architecture can be seen in classical Roman architecture, which effectively continued the earlier designs of ancient Greece. The Romans modified the three contemporary classical orders (Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian) to create two more that were effectively their own—Tuscan, which eliminated the fluting of the Doric order, and Composite, which combined the acanthus leaf ornament of the Corinthian capital with the volutes of the Ionic. Although some ancient Roman architecture copied the preceding Greek style, the Romans mostly innovated new styles of temples, public buildings, and infrastructure.

After the establishment of Byzantium as the capital of the Roman Empire in 330 CE, and before the fall of the western Roman Empire in 476 CE, ancient Roman architecture transitioned into the Byzantine style of architecture. Although the early years of the style were often indistinguishable from late classical Roman architecture, over time it was further abstracted, and eventually the references to ancient Greek architecture became almost unintelligible. Architectural history continued through the medieval styles of Romanesque and Gothic architecture, until the Renaissance began during the 14th century, another important moment in the history of revivalist architecture.

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that sought to return to the perceived sophistication and rationality of the ancient Greeks and Romans, as opposed to what was viewed as the cultural perversion of the Middle Ages. (The term “Gothic architecture” is actually a pejorative coined by the Renaissance humanists—the style was considered to be barbaric and an affront to the refined classical architecture they claimed it replaced. This was a reference to the Goths who caused the fall of the western Roman Empire.) Renaissance architects returned to the strict symmetry and proportions of ancient Roman architecture, as well as their ornamentation and orders. This adherence to earlier spatial and aesthetic principles remained until the Mannerist style originated in the early 16th century, in which architects like Michelangelo played with classical architecture in a proto-Postmodern manner.

The ideals of the Renaissance, however, continued for the next several centuries of architectural history. Mannerism progressed into the ornate Baroque movement in the late 16th century, which further altered the previously staunch classical forms, explosively culminating with the Rococo style of architecture and ornamentation by the early 18th century.

With the advent of Neoclassical architecture after the Rococo movement, a pattern becomes apparent—a new method of design is adopted as a reaction against an earlier architectural style that is perceived as excessive. This was apparent with the transition between Gothic and Renaissance architecture, too, and the same can be said of the transition between late Victorian/Art Nouveau architecture and early Modernist designs. Although Neoclassical architecture uses the same classical ornamentation and proportions of the movements before, it was a response to the extreme level of detail present in late Baroque and Rococo architecture, and it sought to return to a more authentic expression of ancient Greek and Roman architecture.

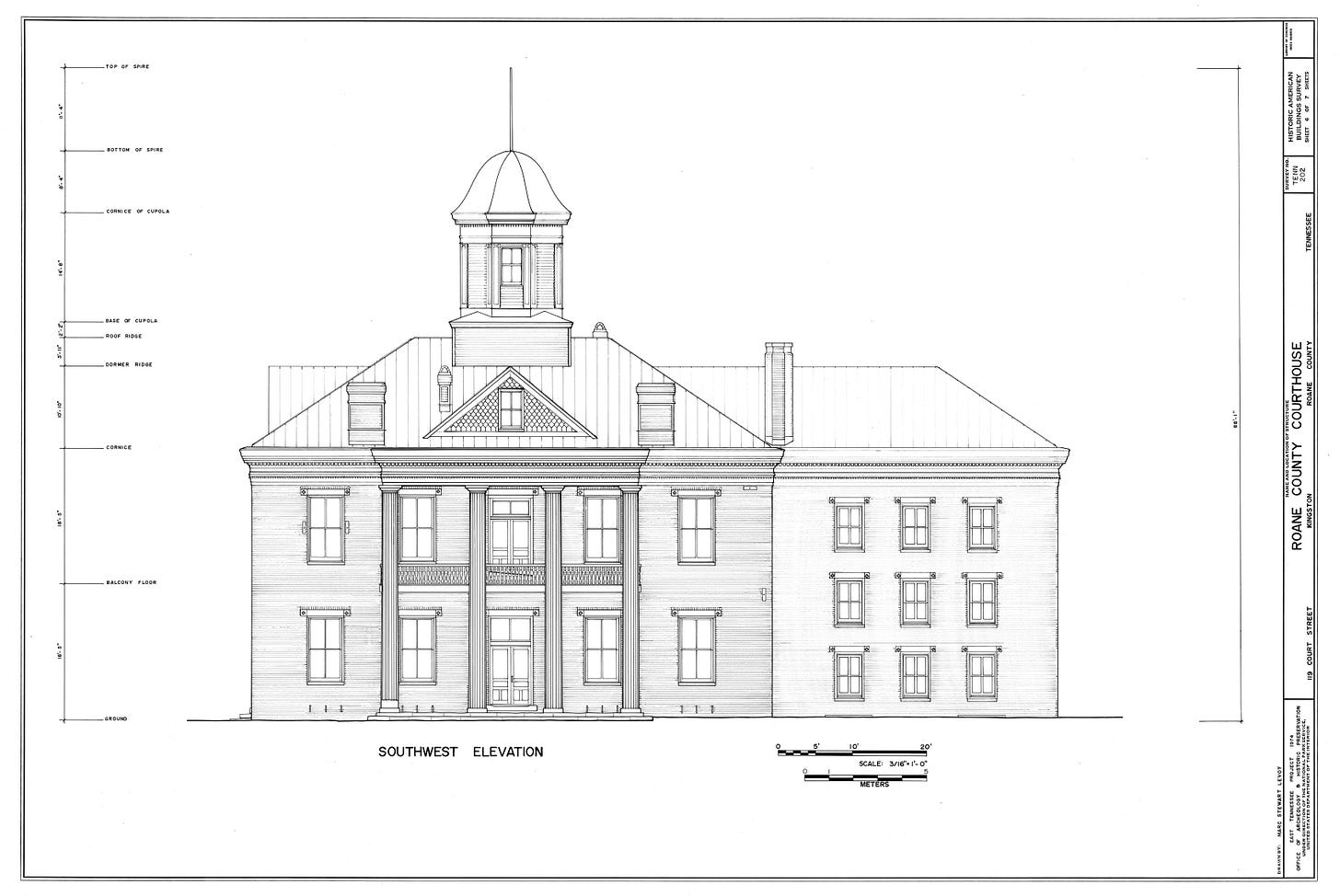

Even the budding United States was not immune to the influence of revivalist architecture. Georgian and Federal architecture, some of the earliest American vernacular styles, were both influenced by the ideals of the Renaissance. As the colonies fought for and won their independence, they were inspired by the political ideas of the Roman Republic, and therefore sought to evoke ancient Roman architecture in the nation’s first government buildings.

The 19th century introduced more exotic revival styles. It goes without saying that Western architecture styles were deliberately revived at first, as opposed to the equally impressive architecture of antiquity in other countries; but as the Romanticist movement began to take root in Europe, various other architectural styles began to see increased interest. The first was likely Gothic architecture, which was resurrected in 1749 with Walpole’s Strawberry Hill House. Others include Romanesque architecture (early 19th century), Renaissance architecture (mid-19th century), and exotic revivals such as Egyptian and Islamic architecture. Architects who designed in the Eclectic style blended multiple different styles together to create an unusual final product.

The Victorian architecture of the late 19th century to the early 20th century was iconic for its heavy ornament and frequent use of revivalist styles. Architects in Chicago pioneered the Chicago School style, which abandoned historic precedent and embraced new technology that allowed for greater height and wider expanses of windows. However, Neoclassical and early Beaux-Arts designs remained prevalent across the country, along with the Gothic and Romanesque Revivals. After the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, which is best known for its iconic Beaux-Arts works of architecture, designing in the classical language once again came back in vogue, much to the chagrin of contemporary architects like Louis Sullivan. The style continued to influence the American architectural zeitgeist until the 1920s.

Historicist architecture’s last pre-Internationalism gasp was the Stripped Classicism movement, which combined the streamlined nature of Art Deco and early Modernist architecture with the grandeur and materiality of the Neoclassical and Beaux-Arts styles. Although somewhat popular in the United States, the style was very prevalent in totalitarian regimes like Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, and the USSR.

Though early Modernism and the later International and Mid-Century Modernist styles spurned historicism and originated as a reaction to the perceived gaudiness of Victorian and Beaux-Arts architecture, designing in historic languages had not completely gone away. New Formalism (covered briefly earlier in the article) was an offshoot style of the period that used the forms and geometry of classical architecture, albeit in a highly abstracted manner.

Revivalist architecture returned once more in the mid-1970s, after Robert Venturi’s disdain for the banality of Modernist architecture spawned the Postmodern movement. Postmodernist architecture plays with the ornamentation and massing of historic architecture styles in a whimsical manner, creating highly unusual compositions.

Although Postmodern architecture is largely out of vogue, a successor is the current New Classical movement, which is the ongoing revivalist style today. It is considered a continuation of Neoclassical and Beaux-Arts architecture, while also striving to return to the local vernacular.

Architecture as Memento — Architectural Preservation

Preserving historic architecture, as opposed to altering/demolishing it, is a pretty new phenomenon. Numerous works of classical architecture were demolished or spoliated throughout history at the fancy of kings and warlords. It was much more frequent that the bigger and better works of architecture simply replaced the old ones.

In the United States, architectural preservation started slowly in the 19th century, with the designation of sites related to the American Revolution as state historic landmarks. The Gilded Age saw grassroots preservation groups being founded in large cities and states. The Historic American Buildings Survey, which began during the Great Depression, documented important works across the United States and served as a useful archive for preservationists.

The extant preservation movement as we know it began with the razing of New York City’s Penn Station in 1963 for the construction of Madison Square Garden. The public and architects alike decried its demolition, but nevertheless the city persisted. This resulted in nationwide support for historic preservation efforts. Today, many cities have a preservation commission, and federal programs like the National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks help protect our architectural heritage.

Architectural preservation and restoration of historic building stock is necessary to properly maintain the character of our cities. Beyond the discussion of aesthetics, many of these properties are historically significant, and their continued destruction is an affront to our heritage. When analyzing the precedents of Modernist architecture, we should be able to visit the Chicago School buildings they were inspired by, instead of studying old pictures before their demolition.

Architecture as Memento — Adaptive Reuse

Adaptive reuse is similar to architectural preservation in that an existing building is being renovated in some manner. However, adaptive reuse often changes the program and architectural details. It is similar to the square vs. rectangle analogy—all adaptive reuse projects are works of preservation, but not all preservation projects are necessarily adaptive reuse.

Adaptive reuse is a process generally reserved for abandoned or obsolete buildings, most commonly older office buildings, factories, and power plants. The new program is often residential or commercial. Adaptively reusing these types of buildings counters urban decay, while encouraging new users to visit or live in an area.

Like architectural preservation, adaptive reuse is likewise a recent phenomenon. The first major project in the United States was San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square, which converted a historic chocolate factory to commercial space in 1964. Common candidates for reuse include industrial properties like mills, factories, power plants, and warehouses. This results in formerly industry-dominated neighborhoods like New York City’s Meatpacking District and Chicago’s Printer’s Row becoming largely residential in the present day.

Adaptive reuse’s flaw is that it can be an agent of gentrification, and it might drive out longtime residents of an area as costs increase. Although renovating disused or obsolete buildings is important, it may come at the price of changing a neighborhood for the worse.

Refreshing Your Memory

With these four tenets of architectural memory, we can return to the Memory Building and analyze how they relate to that work of architecture.

Precedents in terms of early skyscrapers are odd. The building type was being newly invented, and the first examples often took the form of smaller modules being “stacked” on top of each other. However, the Memory Building takes on the Sullivanesque articulation of a classical column, with a “base,” (the first story and raised basement) “shaft,” (the central portion) and “capital.” (the cornice)

The Memory Building was designed in a historical revival style—the Eclectic style, in fact. The arched windows, heavy stone base, and central pediment above the cornice are Neoclassical features, but the ornament and materiality are Romanesque Revival.

Although the Memory Building was not preserved and was demolished shortly after its construction, several of its contemporaries still stand. Preservationists have won many decisive victories to save beautiful and important historic buildings, but many more have been lost to the wrecking ball.

The Memory Building itself did not last long enough to require an adaptive reuse, but the Printer’s Row neighborhood it stood in is an area that has seen many projects of that nature. As the printing companies moved out, they left their offices and warehouses behind, which were converted into lofts starting in the 1980s.

Through these four methods, our architectural memory is inherently involved with any project. Whether restoring or updating an old building, or designing a new one using a revival style or historic architecture as precedent, the past is always present.