The Importance of Landscape in Literature

An insight into how a writer shapes a story with their descriptions of landscape.

Landscapes play a vital role in adding depth, atmosphere, and thematic richness to a story. Far more than just background scenery, a well-crafted landscape serves as a tool for building mood, reinforcing themes, and offering insight into characters' internal lives. Renowned writers like Cormac McCarthy, J.R.R. Tolkien, Jack London, Jean M. Auel, and Mary Oliver have used landscape descriptions to elevate their narratives, transforming setting into an integral part of storytelling. By examining their work, we can see how landscapes function on multiple levels—from guiding the reader's emotions to mirroring the protagonist’s journey.

Setting the Mood and Atmosphere

Landscape descriptions play a crucial role in shaping the mood of a story, subtly steering the reader’s emotional response. By detailing certain aspects of the environment—such as lighting, weather, or sounds—authors can evoke particular feelings that align with the narrative’s themes and tone. For example, in The Road, Cormac McCarthy paints a haunting vision of a post-apocalyptic world through sparse, bleak language that mirrors the characters’ hopelessness and isolation:

“Nights dark beyond darkness and the days more gray each one than what had gone before. Like the onset of some cold glaucoma dimming away the world.”

(Quick note: The Road is the only book that has ever made me cry, highly recommend.)

McCarthy’s minimalist, almost austere prose style reflects the landscape’s emptiness, using descriptions to create a haunting, emotionally charged atmosphere. This sense of a dying world heightens the stakes for the story’s characters, intensifying the themes of survival and resilience.

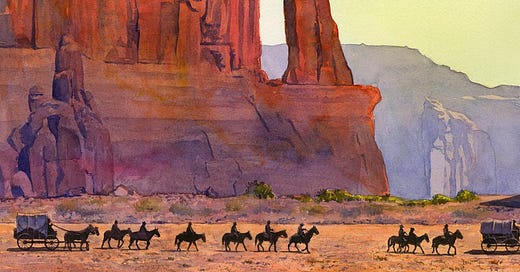

In contrast, McCarthy’s Blood Meridian presents a different use of landscape to establish mood, creating an atmosphere of dread and inevitability through descriptions of a stark, unforgiving desert:

“The desert lay in a sun darkened beyond sunset. The shadowline waiting on the plains drawn across it by the mountains in the east like a curtain and it was as if the last day was upon them all.”

Here, the desert is vast and merciless, setting a foreboding tone that mirrors the violence and moral ambiguity of the story. McCarthy uses landscape to highlight the bleakness and brutality of human nature, making the landscape an active force within the narrative.

Creating a Sense of Place and Immersion

Richly detailed landscapes allow readers to be immersed in a fictional world, making it feel tangible and real. This is especially vital in genres like historical fiction and fantasy, where readers must be grounded in settings that are unfamiliar. In The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien uses landscapes not only to ground his readers in Middle-earth but to communicate the inherent magic and history of the land itself. Consider his description of Rivendell:

“The air was warm. The sound of running and falling water was loud, and the evening was filled with a faint scent of trees and flowers, as if summer still lingered in Elrond's gardens. But all was quiet in the valley.”

Tolkien’s description captures the ethereal beauty of Rivendell, making it feel like a sanctuary outside of time. The sensory details—sound, scent, and warmth—create a vivid, immersive setting that helps readers visualize and connect with this unique world.

In The Two Towers, Tolkien shifts to describe the haunting, eerie Dead Marshes:

“Dreary and wearisome they were, and bitter the smell in the air. Cold clammy winter still held sway in this forsaken country… the mists were thick on the surface of the evil-smelling pools, cold clammy winter still held sway in this forsaken country.”

This desolate landscape, unlike the serene beauty of Rivendell, amplifies the story’s tension and sense of foreboding. By contrasting these places, Tolkien not only builds a fully realized world but also emphasizes the challenges and dangers the characters face as they journey through Middle-earth.

Reflecting Character Emotions

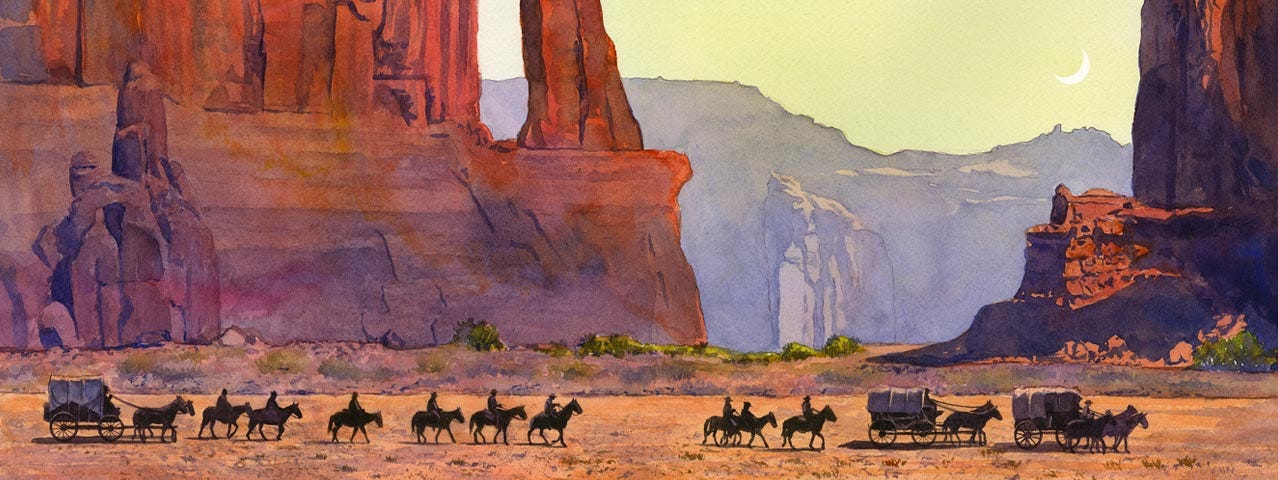

Landscape can act as an external reflection of characters’ internal conflicts or states of mind, enhancing emotional depth. In The Call of the Wild, Jack London uses the harsh, untamed Alaskan wilderness as a mirror for the protagonist, Buck, and his transformation from a domestic pet to a creature of instinct and survival:

“There is an ecstasy that marks the summit of life, and beyond which life cannot rise. And such is the paradox of living, this ecstasy comes when one is most alive, and it comes as a complete forgetfulness that one is alive.”

London’s descriptions of the wild are raw and exhilarating, conveying both the beauty and brutality of Buck’s return to his primal roots. The landscape embodies Buck’s psychological journey as he grows increasingly attuned to his instincts, echoing the themes of resilience and survival.

In White Fang, London again uses the wilderness to reflect a character’s journey, this time tracing the opposite transformation. White Fang, a wolf-dog, experiences domestication, and the landscape shifts from wild, icy expanses to the more controlled environment of human settlements:

“Then one day the sun rose over the edge of the eastern sky and blazed down upon the land till the snow began softly to fall in upon itself and melt. A flood of sunshine poured down upon the land.”

The thawing landscape here symbolizes White Fang’s transition into domestication, mirroring his adaptation to a more ordered, less brutal life. London’s landscapes not only create atmosphere but also serve as metaphors for the characters’ inner journeys.

Modulating Pacing and Narrative Rhythm

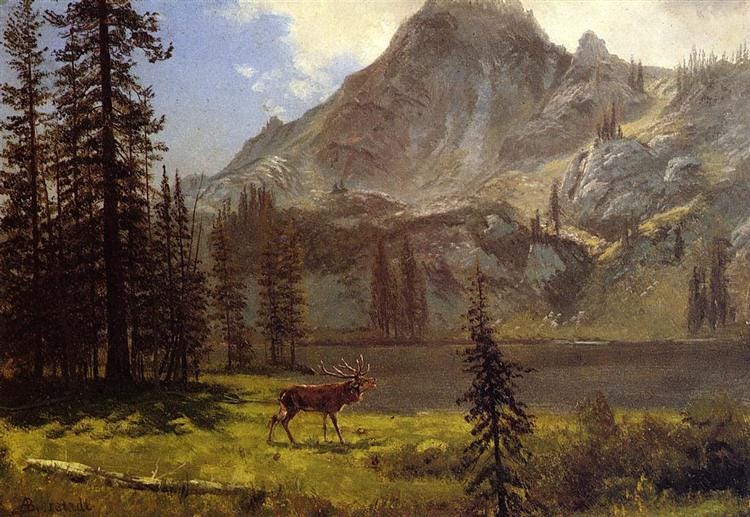

The way an author describes landscapes can also affect the story’s pacing, slowing the narrative for reflection or quickening it to maintain momentum. Jean M. Auel’s The Clan of the Cave Bear utilizes landscape descriptions to establish the Ice Age world, guiding the reader through a prehistoric setting while controlling the story’s tempo. Her descriptions of the steppe allow for a pause, creating a slower, more contemplative pace:

“They left the valley behind and crossed a vast stretch of plains, broken only occasionally by low hills. The steppes were covered with rippling waves of grasses, bending with the wind.”

Auel’s careful, almost scientific descriptions of the land give readers space to absorb Ayla’s world, allowing them to imagine the challenges and beauty of early human life. This slower pace underscores Ayla’s deep connection with nature and reinforces themes of adaptation and resilience.

Similarly, in The Valley of Horses, Auel’s sequel, she uses landscape to set the story’s rhythm, describing the fertile valley that Ayla discovers:

“She looked across the lush green valley, toward the sparkling stream, and inhaled the sweet fragrance of wildflowers warmed by the sun.”

The valley is portrayed as an oasis of safety and abundance, reflecting Ayla’s need for shelter and stability. Auel’s rich descriptions of this landscape, combined with the pacing they create, allow readers to feel Ayla’s sense of relief and belonging.

Reinforcing Thematic Elements

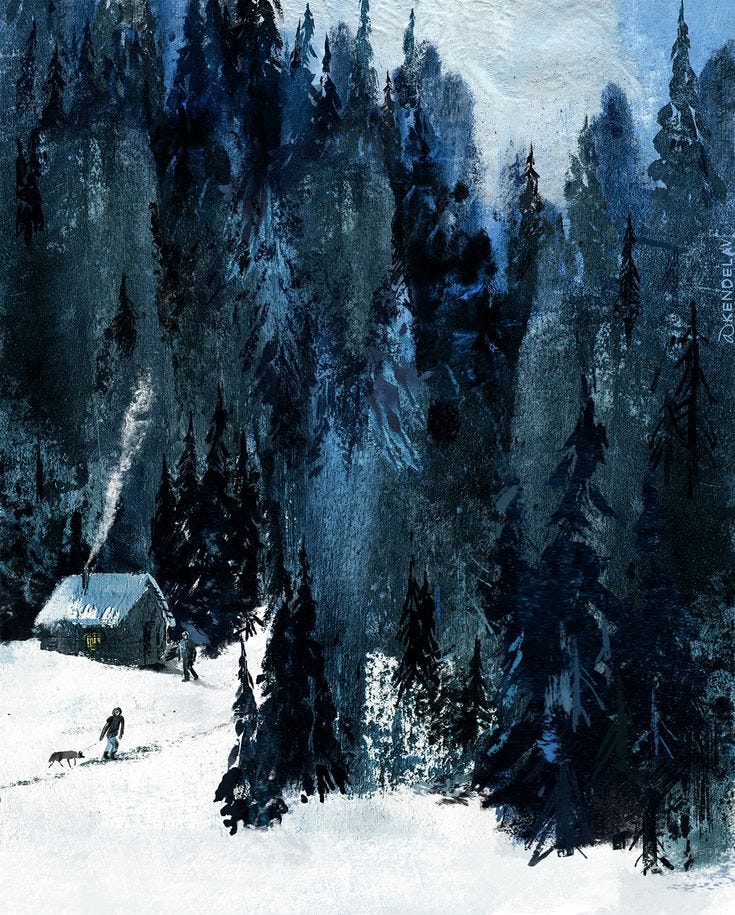

Landscape is also a powerful tool for reinforcing themes, embodying concepts central to a story’s message. Mary Oliver’s work often explores the relationship between humans and nature, treating landscapes as a source of wisdom and spiritual insight. In Upstream, Oliver’s reflections on forests and rivers become meditations on life’s mysteries and the beauty of simplicity:

“I am not a visitor in a forest. When I walk out into the woods, it is always with a sense of leaving the city of the obvious, the common expectation.”

For Oliver, the forest is a sanctuary, a place where she can transcend societal constraints and reconnect with her inner self. Her descriptions of nature reveal her belief in the sanctity of the natural world and its power to guide us back to our truest selves.

In her poem “Sleeping in the Forest,” Oliver’s relationship with nature is again evident as she describes her profound connection to the earth:

“I thought the earth remembered me, she took me back so tenderly, arranging her dark skirts, her pockets full of lichens and seeds.”

Here, Oliver’s landscape is intimate and nurturing, symbolizing themes of belonging and interconnectedness. The forest is more than a physical place; it’s a reflection of her spirituality and reverence for the earth, reinforcing her belief in the unity of all life.

Landscape as Storytelling: Not Just a Backdrop

In the works of Cormac McCarthy, J.R.R. Tolkien, Jack London, Jean M. Auel, and Mary Oliver, landscapes transcend their role as setting to become a vital component of storytelling. Through mood, immersion, character reflection, pacing, and thematic reinforcement, landscapes enhance the emotional and psychological resonance of a narrative. These writers show that the true power of landscape lies not just in describing a scene but in using it to reveal deeper truths about the characters, the themes, and the human condition itself.

In their hands, landscapes are dynamic and alive, inviting readers to journey through settings that shape every aspect of the story. By treating landscapes as integral to the narrative, these authors elevate the setting from background scenery to an essential player, guiding readers toward a richer, more profound experience of the story’s world.

The Road, McCarthy

Blood Meridian, McCarthy

Lord of The Rings, Tolkien

The Two Towers, Tolkien

The Call of The Wild, London

White Fang, London

The Clan of The Cave Bear, Auel

The Valley of Horses, Auel

Upstream, Oliver

Sleeping in The Forest, Oliver

I think this piece sets the stage for more conversations within landscape architecture on how we can better communicate our profession and serve clients. I'm curious as well how often the themes we graphic design in our projects reflect or translate into reality once they are built. If there is a disparity in terms of design and reality, what are ways can we close that gap.