Selling the West

Why the “Big Beautiful Land Bill” is an obvious problem for the heart of America.

Theodore Roosevelt saw conservation not as sentiment, but as duty. This past weekend, that vision faces one of its most alarming challenges. A new provision quietly embedded in a Republican-led “Big Beautiful Land Bill” proposes the sale of more than three million acres of public land across the American West. Marketed as a solution to the housing crisis, this sweeping proposal threatens to dismantle over a century of conservation work, handing vast swaths of wild land to private interests in what critics are calling the largest land sell-off in modern U.S. history.

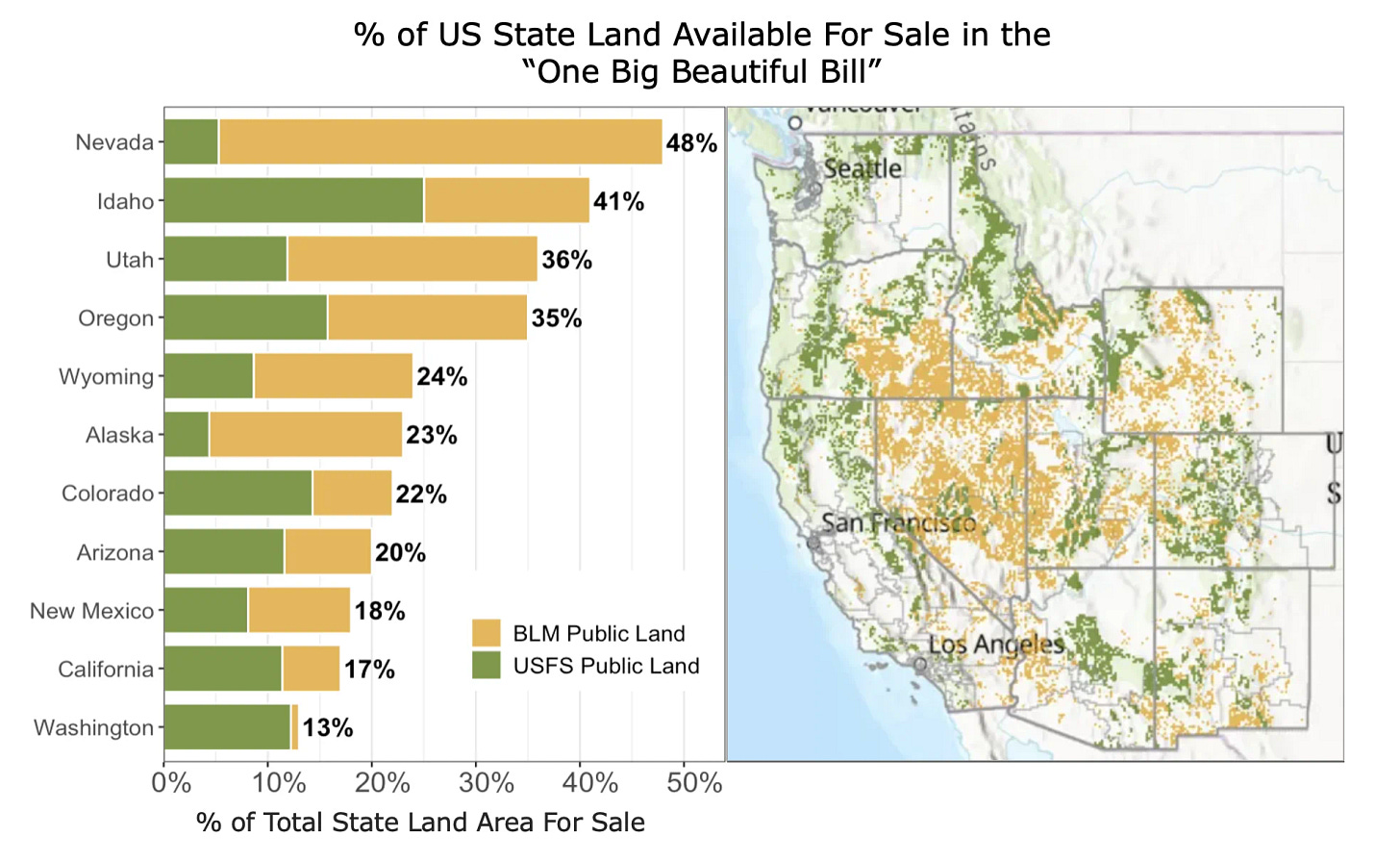

In the latest wave of policy maneuvers emerging from Washington, Republican lawmakers spearheaded by Utah Senator Mike Lee have introduced a provision that could lead to the sale of over 3 million acres of public land across the American West. Marketed as part of a broader “Big Beautiful Land Bill,” this proposal is being touted as a solution to the housing crisis, a boost to local economies, and a corrective to federal overreach.

But underneath the surface-level appeal lies a plan with profound consequences. If passed, this bill could dismantle decades of conservation work, dispossess Indigenous communities of cultural and ancestral lands, and permanently alter the ecological integrity of some of the last truly wild spaces in the United States. And all of it is being done with little public input and under the misleading banner of economic revitalization.

The Quiet Dispossession of Public Land

At the center of the bill is a provision to force the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and U.S. Forest Service to identify and sell “isolated or underutilized” parcels of land. This would affect millions of acres in eleven Western states, including California, Utah, Colorado, Oregon, Idaho, and Wyoming.

Supporters, including Sen. Lee and his Republican colleagues, frame the land sales as “common sense” steps to unlock economic potential in remote regions. They argue that these parcels aren’t used for public recreation or environmental protection, and could instead be repurposed for housing, infrastructure, or private development. Ninety-five percent of the revenue would go directly to the U.S. Treasury, framed as a windfall for taxpayers.

Yet, this logic ignores the role these lands play in the American landscape. They are often wildlife corridors, grazing areas, migration zones, Indigenous sacred sites, and key buffers against climate disruption like wildfires and drought. Their so-called “isolation” is precisely what gives them value ecologically, spiritually, and recreationally.

A Death Blow to Conservation Progress

The idea of liquidating federal lands isn't new. It echoes the “Sagebrush Rebellion” of the 1970s and ’80s, where Western conservatives pushed to devolve land management from federal to state control. But this proposal goes much further, threatening direct privatization with no guarantee that the land will remain accessible to the public.

Unlike earlier land transfers governed by safeguards like the Federal Land Transaction Facilitation Act (FLTFA), which ensured sale revenues were used to acquire and protect more valuable conservation land, this bill offers no such mechanism. The lands could be sold to the highest bidder, with no restriction against resale or development.

That means logging firms, mining companies, or real estate developers could acquire the land, fence it off, and pave it over with luxury homes or extractive infrastructure, forever locking Americans out of their natural heritage.

Threats to Native Sovereignty and Sacred Landscapes

Many of the affected parcels lie on or adjacent to lands of cultural significance to Native American tribes. Under the current framework, the Department of the Interior and the Department of Agriculture are only required to “consult” tribes with no obligation to follow their input or consider the historical trauma of land dispossession.

For tribes like the Shoshone, Ute, Paiute, Hopi, and Apache, these lands are not “unused parcels” but sacred geographies with oral histories, ceremonial importance, and ecological stewardship stretching back millennia. That history is at risk of being bulldozed again.

The proposed land sale also violates the spirit, if not the letter, of treaties and federal trust responsibilities. While the Biden administration has made strides in co-management and land rematriation efforts (such as returning lands in Bears Ears and Avi Kwa Ame), this bill moves sharply in the opposite direction, in turn fueling distrust and resentment among Indigenous nations.

Ecological Fragility and the Climate Crisis

From the Sierra Nevada to the high desert plateaus of Utah and Colorado, the lands now on the chopping block are some of the most climate-vulnerable in the country. They provide habitat for endangered species, sequester carbon, and act as ecological buffers in the face of increasingly severe wildfires and droughts.

Many of these areas are home to old-growth forests, wetlands, and riparian zones, places not only rich in biodiversity but crucial to the overall health of American ecosystems. Selling these lands to private owners opens the door to fragmentation, pollution, habitat collapse, and fire-prone development patterns.

I would argue that using housing affordability as the rhetorical hook is especially disingenuous. Most of the parcels being considered are far from infrastructure, in remote, high-desert areas where developers are unlikely to build affordable homes. Instead, they’ll build second homes for the wealthy, extractive facilities, or resorts, leaving working-class and Indigenous communities more vulnerable than before.

Who’s Really Benefiting?

While there’s no confirmed evidence that firms like BlackRock are directly lobbying for the bill, the policy aligns with the general direction of real estate speculation and corporate land acquisition across the U.S. The bill offers a new pipeline for land to move from public to private hands with minimal oversight and maximum investor gain.

Behind the scenes, influence appears to be coming from the oil and gas sector, which has donated heavily to Republican senators like Mike Lee. Industry allies see public lands as underutilized assets ripe for drilling, fracking, and extraction under looser regulatory frameworks.

Even some Republicans are beginning to question the wisdom of the bill. Senator Steve Daines of Montana and Representative Ryan Zinke (himself a former Interior Secretary) have expressed concerns about the loss of access for sportsmen, ranchers, and rural communities.

Public Backlash Builds

Local communities, especially in places like Northern California, Idaho, and Oregon, are beginning to organize against the bill. In a surprising twist, some of the fiercest opposition comes from conservative-leaning counties where public lands are considered vital to recreation-based economies and rural identity.

Groups like the Center for Western Priorities, the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, and Patagonia are rallying public awareness campaigns, warning that the bill could lead to irreversible loss of public space. Even the name of the bill—“Big Beautiful Land Bill”—has been criticized as Orwellian: a shiny wrapper hiding a deep betrayal of public trust.

A Watershed Moment

This isn’t just about some obscure parcels in the high desert. This bill represents a watershed moment in the history of American land policy. It challenges fundamental ideas about who owns the land, who has the right to access it, and what kind of future we want to build in the face of ecological collapse and rising inequality.

As it stands, the proposal reflects a dangerous philosophy: that nature is a commodity, public goods are expendable, and long-term sustainability is less important than short-term profit. It’s a test of political will, one that will determine whether our public lands remain a shared birthright, or become just another asset class on the market.

For conservationists, Native tribes, ecologists, and ordinary Americans who treasure these landscapes, the message is clear: now is the time to speak up. Because once the land is gone, it won’t come back.