Inefficiencies of the Mississippi River Delta

Many methods used to control coastal flow are outdated, and now more than ever are they failing us. How are design students tackling the issue? Read how by Wesley Cogan from Issue 8, Spring 2014

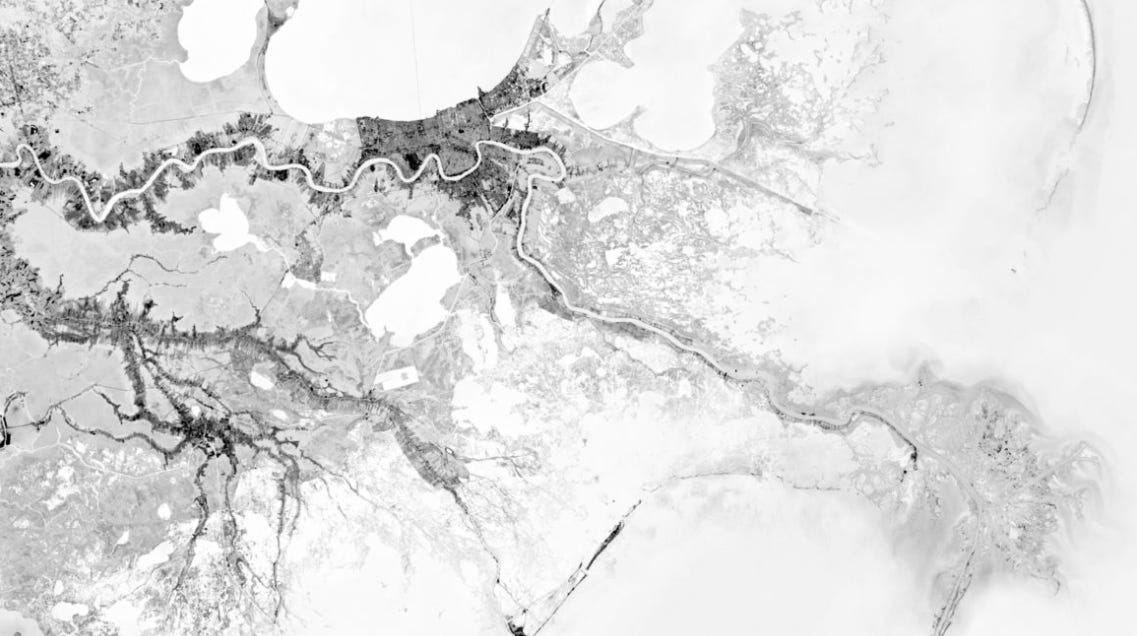

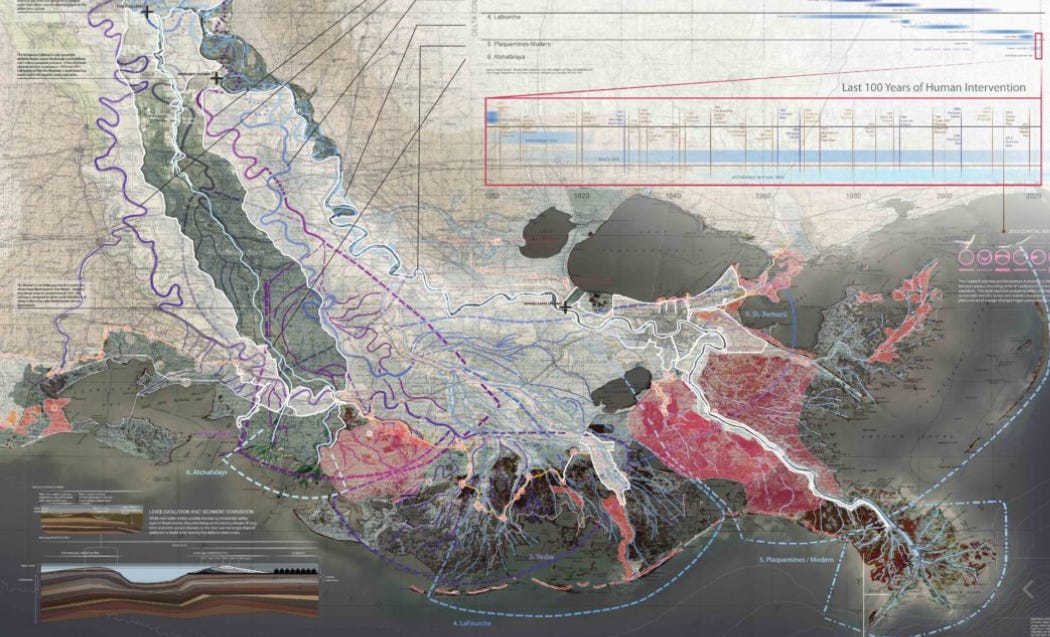

The state of Louisiana loses a football field of land every 15 minutes, which accounts for 80% of the nation’s coastal wetland loss. This staggering disappearance is largely due to human and natural disturbances such as levee construction, canal dredging, hurricanes, and rising sea levels. In response, state and federal governments have passed numerous acts in order to mitigate the processes in play and in turn grow land. But land will continue to be lost as the geomorphological processes grow insurmountable. It is crucial for the effort to maintain and reclaim these lands to achieve maximum productivity with minimum wasted effort or expense. A current strategy called bay bottom terracing utilizes backhoes anchored to barges push and shape existing sediment. The resulting forms harbor wetlands and marshes, which in turn trap additional sediment as it enters the Mississippi River Delta and ultimately build land.

Bay bottom terraces created according to existing methods appear as oddly rectilinear forms, clone stamped across the delta and limited by the motions of the tool which creates them. Arguably, this strategy is ‘efficient’ in terms of distribution: the barge travels in a linear trajectory which is both cost and time effective. But should this efficiency of distribution be the sole driver of the enterprise? Bay bottom terracing is a prolific method of land production on the coast. Is it possible to improve bay bottom terracing with simple interventions, while maintaining its effort and expense efficiencies?

As martin Ruess stated in The Art of Scientific Precision: River Research in the United States Army Corps of Engineers to 1945, “The technologies to control river (coastal) flow have not changed fundamentally for ages. They include dams, levees and floodwalls, bank revetment, jetties, channel stabilization, and dredging. The emphasis is on the effective application of existing technologies; the innovation usually is in the details.” Ruess suggests that river control technologies are not processing — and perhaps the key to innovation is an emphasis shift from macro to micro scale.

DredgeFest Louisiana, a symposium and speculative design workshop about the human manipulation of sediments, was held by the Dredge Research Collaborative in January 2014 on the Louisiana State University campus in Baton Rouge. Participants challenged existing sediment control technologies by designing new methods and comparing their efficiencies. The workshop ‘Hybrid Morphologies’ lead by Alex Robinson and Richard Hindle focused specifically on the bay bottom terracing practices occurring in two sites: Vermillion Bay and Pecan Island. Participants explored alternative terracing practices through a highly generative process, pairing the physical modeling of sand with digital analysis through Grasshopper. The typical terracing process utilizes a simple tool, a backhoe attached to a barge which moves linearly. Workshop participants quickly developed and fashioned new ‘tools’ out of chipboard, foam core, and wooden dowels, and then tested these tools against the properties of sand in miniature sandboxes. The sand modeling explorations worked amongst the constraints of the linear barge trajectory, while experimenting with alternative terrace forms and patterns. The resulting sand model forms were then 3D scanned, generating a 3D Rhino model that could be analyzed utilizing Grasshopper scripts.

The formations were tested on measures of slope percentages, surface area, and wave and wind exposure. In all cases the new methods proved more effective in land building than the current rectilinear forms. The newly developed forms, although visually complex, would take a comparable amount of effort in terms of barge operation and time needed. The generated forms would provide a greater surface area than current strategies, allowing for increased vegetation density and improved structural integrity. The workshop concluded with the consensus that a simple technology change, at no expense to the internal efficiency of the Army Corps of Engineers, would greatly increase the production of land.

Although the current practices of bay bottom terracing may produce results in a manner internally efficient to the Army Corps of Engineers, the more significant efficiency is that of the resulting system. Further exploration may lead to resulting forms which develop stable land at faster rates. Such interventions will help define a more robust geomorphology for the future of the Mississippi River Delta.

Past Issues

This article is a part of One:Twelve’s “From the Archives” series, selecting some of our favorite pieces since the magazine’s start in 2010.